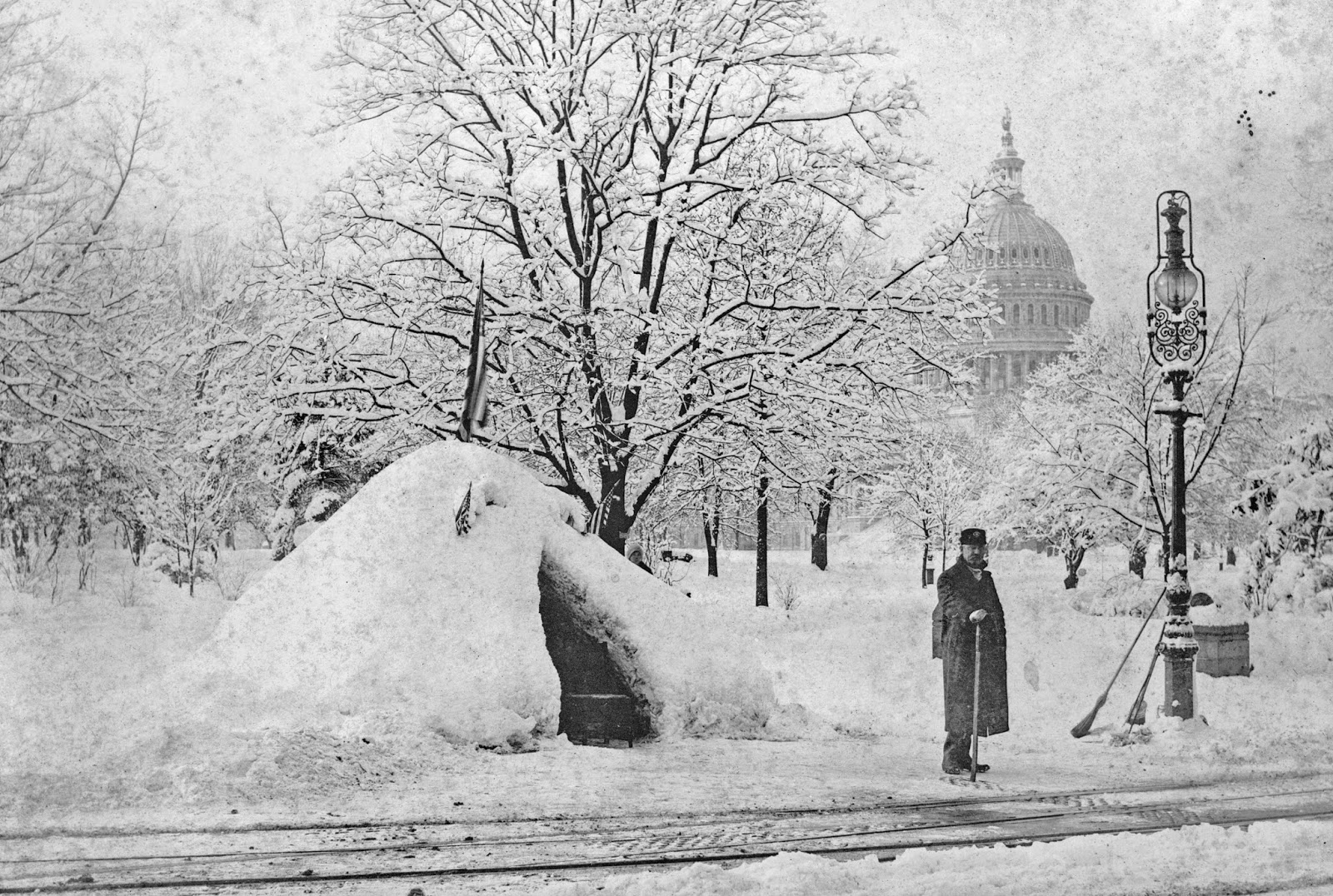

Although the snowstorm that just struck the east coast was not as bad as forecasters feared, it's worth looking back at one of the most devastating storms from the past. The great blizzard of March 11, 1888 wasn't even predicted at all in Washington. The weather forecast that day was just for wind and rain, with clear skies to follow. Sure enough, the day began with heavy rains, but by late afternoon it turned suddenly to heavy snow. About a foot of snow fell through the night, followed by fierce winds. It turned out to be a cataclysmic storm, walloping the entire northeastern U.S. and dumping two to three feet of snow in New York and New England. Though Washington was not the worst hit, the storm's effects had a lasting impact on the city.

"The storm that visited Washington yesterday was one of the most remarkable known for years, The Evening Star reported on Monday, "In fact, the capital seemed to have dropped into the very center of a cyclone that brought with it a blinding succession of rain, snow, wind, and cold.... [T]he city was sheeted in a mantle of white that grew thicker every minute. As the night fell the heavily-laden telegraph wires began to come down, and in many places the streets were blockaded so that street cars had to turn around and make partial trips. The police wires were out of order, and to add to the discomforts of the night the electric lights began to fail. By midnight the city was almost in darkness, save for a few feeble gas jets that had flickered through the storm."

The combination of rain, snow, and high winds proved especially disastrous for communications, as hundreds of telegraph and telephone poles, laden with wet snow and ice, were easily blown down by the wind. Washington was thoroughly cut off from the outside world in a way it had not known since before the Civil War. No power, no lights, no communications. Police patrols were incommunicado and fire alarms could not be turned in. According to the Star, On B Street [now Constitution Avenue], from 6th to 9th streets northwest, nearly all the telegraph poles were broken about 15 feet from the ground, and the cross-arms and wires formed a net work across the street, making it impossible for the street cars to pass.... The wires connecting the police patrol boxes were either crossed or broken, and all persons arrested had to be marched through the streets in the old-fashioned way." The Washington Post put it more starkly: "Fires, murders, riots or any species of disturbance might have taken place in the remote sections of the city and no assistance could have been summoned."

The Star's observation that Washington seemed to be at the "very center" of the cyclone betrayed how little Washingtonians knew about the extent of the storm they had just survived. In fact, Washington was at the southern end of a massive system that had walloped the entire Eastern seaboard, dumping two to three feet of snow in New York and New England and killing several hundred people there. Washington had gotten off comparatively easy.

It certainly didn't seem that way, however. At the railroad depots, which were so vital for the city's commercial life in those days, no trains had shown up for many hours. The timetable boards that normally displayed dozens of arrivals and departures said merely "We don't know anything." Trains were delayed not just from the snow itself but from all the telegraph poles and wires strewn over the tracks for many miles.

"While the amount of damage cannot be accurately estimated it is certain that not in years has the city been visited by a storm that caused more trouble or endangered life and property as much as did the storm of yesterday," the Post concluded.

The city's half dozen streetcar lines struggled to get their own tracks cleared but were generally successful when telegraph poles didn't block their paths, and service was nominally up and running on many routes. But keeping the cars moving proved to be a daunting task. Washington's street cars in 1888 were still all horse-drawn, and the operators had to stand on open platforms at the front of the cars. Man and beast both suffered mightily in the howling wind and frigid cold.

While most people stayed home, some events went forward as planned. Georgetown University Medical College held its graduation ceremonies at Albaugh's Grand Opera House on Pennsylvania Avenue for its class of 12 new doctors. Rev. J. A. Doonan, president of the university, pointed out helpfully to the budding physicians that "even a day like yesterday was good for pneumonia."

Then on Tuesday, two days after the storm passed, the winds picked up again. Western Union's linemen had to suspend their repair work on the telegraph lines in the face of 40 mile-per-hour winds, and much of the early repair work from Monday was ruined again. Train travel to and from Philadelphia or points farther north was still impossible. Even water travel had been stymied. "Navigation on the [Potomac] river is as much impeded as is the traffic on the railroads. The wind has literally blown all the water out into the [Chesapeake] bay, and the steamers were unable to leave their wharves [along the Southwest waterfront], the Post reported. "The river presented a curious appearance yesterday. The water was so low that brown banks of earth were visible along every side and [the river] seemed to have diminished to half its usual width." Gleeful scavengers happily scoured the newly exposed banks for tools and other long-lost artifacts.

After a few more days, warm weather arrived, and the snow began to disappear quickly, as it often does in Washington. Workers cleared away debris and re-established communications lines, shocking Washingtonians with the news from up north, where the toll had been so much worse. When it was all over and finally cleaned up, the great snow storm of March 1888 left at least one lasting imprint on many Washingtonians: it showed how foolhardy it was to rely entirely on communications systems that used overhead wires. The Evening Star's outspoken editor, Crosby S. Noyes (1825-1908) began a long campaign to have electric wires buried within the downtown area of the city.

Coincidentally, in October 1888, the first electric streetcar line, The Eckington and Soldiers' Home Railway, began service, and it used overhead wires. Noyes was livid. He won the support of influential congressmen and senators, many of whom undoubtedly remembered all the downed poles and wires from the great blizzard in March. Noyes ultimately was successful in having all wires buried in downtown Washington. The Eckington line would be the only one in the central part of the city to use overhead wires. All of Washington's future streetcars would get power from an underground conduit, accessed through a center slot between the rails. The blizzard of 1888 certainly wasn't the only reason this happened, but it drove home the value of underground systems in a most dramatic way.

Sources for this article included Kevin Ambrose, Blizzards and Snowstorms of Washington, D.C. (1993); and numerous newspaper articles.

To receive Streets of Washington by email:click on this link and choose "Get Streets of Washington delivered by email" from the Subscribe Now! box on the upper right hand side of the page.![]()

|

| A street-side snow hut made after the massive snow storm of March 1888 (Source: Library of Congress). |

"The storm that visited Washington yesterday was one of the most remarkable known for years, The Evening Star reported on Monday, "In fact, the capital seemed to have dropped into the very center of a cyclone that brought with it a blinding succession of rain, snow, wind, and cold.... [T]he city was sheeted in a mantle of white that grew thicker every minute. As the night fell the heavily-laden telegraph wires began to come down, and in many places the streets were blockaded so that street cars had to turn around and make partial trips. The police wires were out of order, and to add to the discomforts of the night the electric lights began to fail. By midnight the city was almost in darkness, save for a few feeble gas jets that had flickered through the storm."

The combination of rain, snow, and high winds proved especially disastrous for communications, as hundreds of telegraph and telephone poles, laden with wet snow and ice, were easily blown down by the wind. Washington was thoroughly cut off from the outside world in a way it had not known since before the Civil War. No power, no lights, no communications. Police patrols were incommunicado and fire alarms could not be turned in. According to the Star, On B Street [now Constitution Avenue], from 6th to 9th streets northwest, nearly all the telegraph poles were broken about 15 feet from the ground, and the cross-arms and wires formed a net work across the street, making it impossible for the street cars to pass.... The wires connecting the police patrol boxes were either crossed or broken, and all persons arrested had to be marched through the streets in the old-fashioned way." The Washington Post put it more starkly: "Fires, murders, riots or any species of disturbance might have taken place in the remote sections of the city and no assistance could have been summoned."

The Star's observation that Washington seemed to be at the "very center" of the cyclone betrayed how little Washingtonians knew about the extent of the storm they had just survived. In fact, Washington was at the southern end of a massive system that had walloped the entire Eastern seaboard, dumping two to three feet of snow in New York and New England and killing several hundred people there. Washington had gotten off comparatively easy.

It certainly didn't seem that way, however. At the railroad depots, which were so vital for the city's commercial life in those days, no trains had shown up for many hours. The timetable boards that normally displayed dozens of arrivals and departures said merely "We don't know anything." Trains were delayed not just from the snow itself but from all the telegraph poles and wires strewn over the tracks for many miles.

"While the amount of damage cannot be accurately estimated it is certain that not in years has the city been visited by a storm that caused more trouble or endangered life and property as much as did the storm of yesterday," the Post concluded.

|

| A Washington streetcar battles a snowstorm in 1889. (Source: Library of Congress). |

While most people stayed home, some events went forward as planned. Georgetown University Medical College held its graduation ceremonies at Albaugh's Grand Opera House on Pennsylvania Avenue for its class of 12 new doctors. Rev. J. A. Doonan, president of the university, pointed out helpfully to the budding physicians that "even a day like yesterday was good for pneumonia."

Then on Tuesday, two days after the storm passed, the winds picked up again. Western Union's linemen had to suspend their repair work on the telegraph lines in the face of 40 mile-per-hour winds, and much of the early repair work from Monday was ruined again. Train travel to and from Philadelphia or points farther north was still impossible. Even water travel had been stymied. "Navigation on the [Potomac] river is as much impeded as is the traffic on the railroads. The wind has literally blown all the water out into the [Chesapeake] bay, and the steamers were unable to leave their wharves [along the Southwest waterfront], the Post reported. "The river presented a curious appearance yesterday. The water was so low that brown banks of earth were visible along every side and [the river] seemed to have diminished to half its usual width." Gleeful scavengers happily scoured the newly exposed banks for tools and other long-lost artifacts.

|

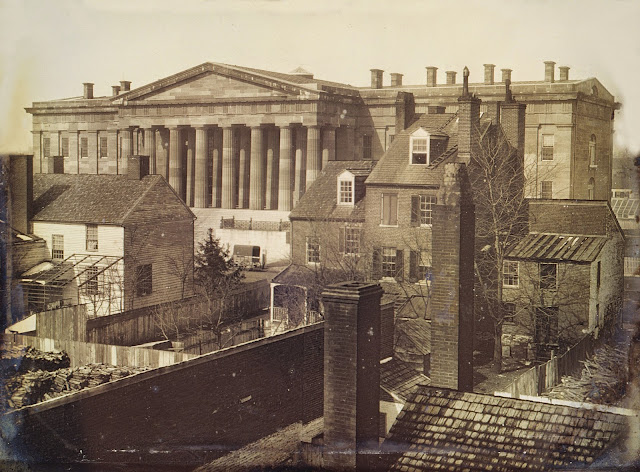

| A horse-drawn sleigh and streetcar cross paths in front of the Ebbitt House hotel in 1889 (Source: Library of Congress). |

Coincidentally, in October 1888, the first electric streetcar line, The Eckington and Soldiers' Home Railway, began service, and it used overhead wires. Noyes was livid. He won the support of influential congressmen and senators, many of whom undoubtedly remembered all the downed poles and wires from the great blizzard in March. Noyes ultimately was successful in having all wires buried in downtown Washington. The Eckington line would be the only one in the central part of the city to use overhead wires. All of Washington's future streetcars would get power from an underground conduit, accessed through a center slot between the rails. The blizzard of 1888 certainly wasn't the only reason this happened, but it drove home the value of underground systems in a most dramatic way.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included Kevin Ambrose, Blizzards and Snowstorms of Washington, D.C. (1993); and numerous newspaper articles.

* * * * *

To receive Streets of Washington by email:click on this link and choose "Get Streets of Washington delivered by email" from the Subscribe Now! box on the upper right hand side of the page.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)